Introduction of working with struct

Introduction

Before C# 7.2 and .net core 2.1, you could improve .net performance with a good dose of conscious effort and relying on code that would not necessarily be nice to look at (and certainly maintainable). Microsoft made several improvements to make sure that you could design & write faster code, not at the sake of the good practices.

Struct, struct and more struct!

It is important to get rid of this reflex of choosing the class keyword every time you design a new type.

Question yourself about if object-oriented programming is really necessary or if you should use another paradigm that would be more data driven.

Using struct has game changing advantages: You don’t directly allocate on the heap, so you’re not using the GC.

You can design a memory friendly layout for your type, avoiding many memory indirection that would increase the chances of cache miss!

Before C# 7.2, relying on struct were not necessarily a performance win, the reason was that each time you passed/return a struct based object: a copy would be made, on the stack, but still a copy is a copy: it takes time!

It is now possible to pass/return struct based objects using reference to the initial object: avoiding an unnecessary and costly copy.

Two know languages keywords ref and in enable many new patterns to speed things up!

Relying on struct will also enable a linear memory layout for your data, making things way more CPU cache friendly.

Let’s take an example:

public class A

{

public int val1;

public int val2;

}

public class B

{

public float f1;

public float f2;

public A a1 = new A(); // Point to another object: another memory location

public A a2 = new A(); // Same here

}

// Allocate an array of 256 pointers to 256 distinct instances of B

var data = new B[256];

data is one object allocated on the heap (GC), it references 256 instances of B, each also allocated on the heap. Each instance of B references two instances of A, also on the heap.

So we have a total of 1 + 256 + 2*256 objects allocate on the heap: 769 objects, each located somewhere in the memory, that will be eventually garbage collected when no longer needed.

Things to note:

- You stress your GC. It could be fine if the life time of all these objects is big, close to static. But if you’re doing some high frequency code and you allocate

datahundred, thousand of time per second: it will have an impact on performances. - Let’s pretend you want to access all fields (direct and indirect) for

data[0]anddata[1]. You will have to fetch 7 separate memory locations (thedataarray,data[0],data[0].a1,data[0].a2,data[1],data[1].a1,data[1].a2).

Let’s make the following changes: we no longer use class, but struct instead.

public struct A

{

public int val1;

public int val2;

}

public struct B // Size of the type: 24 bytes

{

public float f1; // Offset 0

public float f2; // Offset 4

public A a1; // Offset 8

public A a2; // Offset 16

}

// One single memory block of 256 * 24 bytes

var data = new B[256];

Ok, this is a naive explanation, internally .net will make things a bit different, but you get the point:

- We now have 1 object allocated on the heap (

data), which allocates a continuous memory surface block to sequentially store all instances ofB. Bno longer reference other objects: thea1anda2fields are part ofB, not referenced byB.

A foreach on the class version with access to all the fields would have lead to deal with 769 distinct memory locations, with a CPU that would have hard time to prefetch to reduce the time to access the data.

A foreach on the struct version with access to all the fields would be as fast as it could be: there’s one memory block, the CPU understand pretty quickly that we’re sequentially accessing the data, so the prefetch and cache loads are very efficient, because everything was design for this!

Benchmark of class versus struct

I’ve created a small project in order to demonstrate what was explained above, you can go grab it and play with it or just keep on reading.

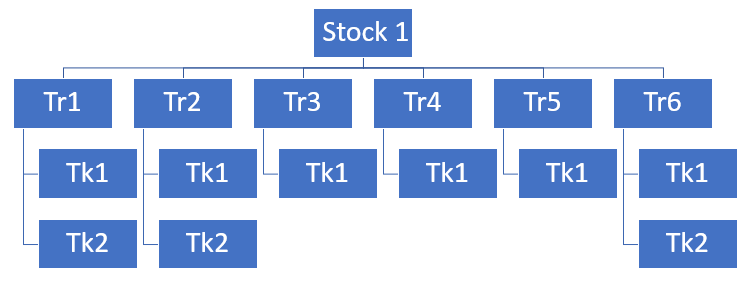

There are two implementations of a simple program which has to deal with a Financial Stock, containing a list of Trades, each Trade also contains a list of Tickets.

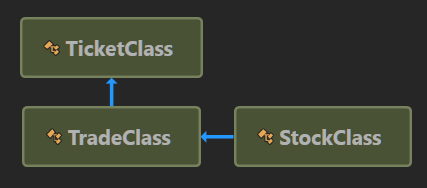

Diagram of the class version

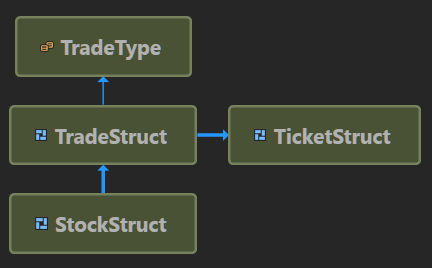

Diagram of the struct version

(don’t mind about the TradeType enum, it’s not important here)

The program

The program file is fairly simple:

- It creates one Stock.

- Generates 1000 Trades to buy or sell some quantity of this Stock.

- Each Trade resulted in one to many Tickets with a given quantity for a given price. The sum of all the ticket’s quantity match the requested one for the Trade.

The program creates the class version and the struct one.

We are going to bench an operation that will compute the average buy price and average sell price for all the Tickets.

So basically:

- We parse all the tickets of all the trades

- Multiply their price with their quantity

- Divide the total buy price by the total buy quantity, same for sell.

In other words we parse the whole tree hierarchy of instances and perform basic computation on it.

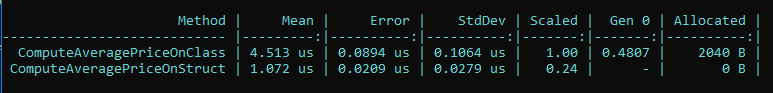

Here is a result of the benchmark comparing the class version against the struct (using BenchmarkDotNet)

Few facts:

- The

structversion is 4 times faster than theclassone, take a look at the Scaled column, theclassversion is the baseline, so its value is1.00, thestructversion is running at0.24time compared to the baseline. - There’s no Garbage Collection on the

structversion, for a pretty obvious reason. - The

classversion has some Garbage Collection and extra allocated memory.

Let’s be clear: this benchmark is not including the construction of the objects, this is done in a setup phase that is not benchmarked. Here, we are only profiling the computation of the average prices.

So why is this 4 times faster considering the fact we’re not creating objects, only parsing them? Well the reason is the one explained in the first post of the series: struct are more memory friendly.

Let’s explain a bit

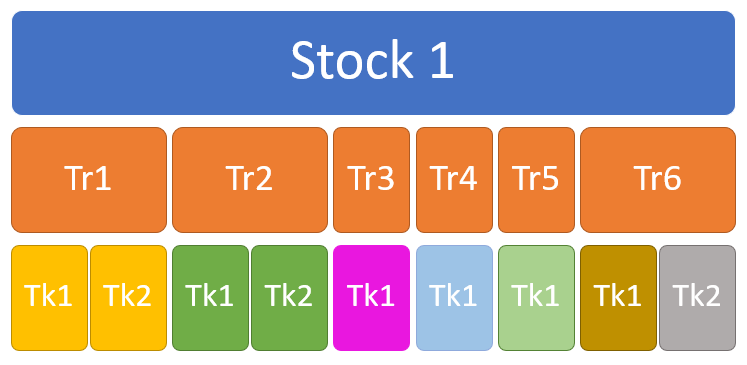

Memory layout for the struct version

In the diagram above, each color represent a memory location.

What is important to understand is:

- All Trades (Tr1…Tr6) objects are stored in an array (stored, not referenced!), so they are in a contiguous memory zone. A For/Loop on them will be pretty efficient as the CPU will quickly fetch the Trade n+1 while we’re processing the Trade n.

- Same thing for the Tickets, but only for the ones that are owned by the same Trade: each Trade has an array containing the Tickets it owns.

In our case there’s 1000 Trades objects that are in a contiguous memory location: this is very memory friendly!

In the program, on average there are 5 Tickets per Trade, it is also apparently enough to be memory friendly.

We could have pushed things further and store all Tickets for all Trades in the same array, but things would be a bit more difficult, let’s keep it simple for now.

Memory layout for the class version

Well, no need of color this time, each object is stored in a distinct memory location, determined by heap manager of the .net CLR.

What is important to understand here is:

- You have no control/guarantee of where the objects are stored compared to the others, which is not good when you care about performances.

- Each object has a distinct lifetime, which is good, but it comes with a price.

A design choice to make

Again, there are no silver bullet: to gain something you have to give up something else in return.

In our case this more about a design decision to make:

- You could easily have everything stored as objects in the heap, this is easy and it’s very “C#”, but performances will be what they are: average for .net.

- You can decide from the start how your objects will be stored, to improve performances, at the expense of some programming flexibility/simplicity.

There’s a saying out there which warns every programmer:

“Early optimization is the root of all evil.”

This is a simplified version of a quote from the great Donald Knuth:

“The real problem is that programmers have spent far too much time worrying about efficiency in the wrong places and at the wrong times; premature optimization is the root of all evil (or at least most of it) in programming.”

Early optimization is not the root of all evil, most of the time, it will be for sure. Optimizing something that won’t worth it is one of the biggest mistakes we all did (and still do, because, you know, it’s fun, it’s challenging!).

However, there are some profound design choices that have to be made from the start, because after, it will be too late!

Ok, that’s all for this post, in the next one we will take a closer look at the code, how to design and program things in order to achieve better performances!

UPDATE #1 on April the 5th

As Marko Lahma pointed out in the comment, the class/struct benchmark is not a fair one, I rely on foreach for classes, because, well, daily habits. This is what generated the 2040 B of Allocation and the Gen 0 GC. The speed difference was bigger than I expected, but mainly because the test is doing pretty much nothing in the nested for/loops (and the GC surely impacts overall performances).

Here’s the result.

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Scaled | Gen 0 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComputeAveragePriceOnClass | 4,083.4 ns | 13.766 ns | 12.877 ns | 1.00 | 0.4807 | 2040 B |

| ComputeAveragePriceOnClassNoEnumerator | 2,807.9 ns | 27.279 ns | 25.517 ns | 0.69 | – | 0 B |

| ComputeAveragePriceOnStruct | 850.5 ns | 4.484 ns | 3.500 ns | 0.21 | – | 0 B |